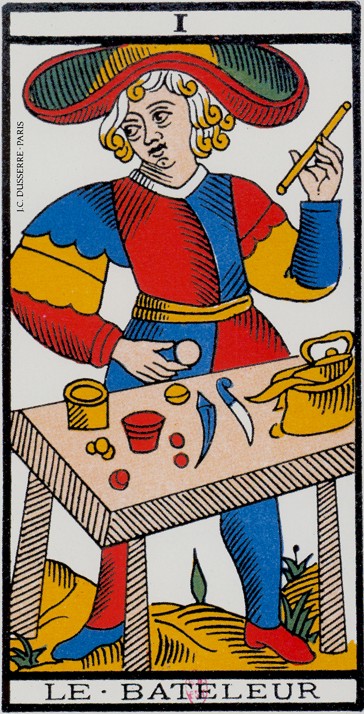

The Tarot of Marseilles or Tarot of Marseille, also widely known by the French designation Tarot de Marseille, is one of the standard patterns for the design of tarot cards. It is a pattern from which many subsequent tarot decks derive.

Michael Dummett’s research led him to conclude that (based on the lack of earlier documentary evidence) the Tarot deck was probably invented in northern Italy in the 15th century and introduced into southern France when the French conquered Milan and the Piedmont in 1499. The antecedents of the Tarot de Marseille would then have been introduced into southern France at around that time.

The game of Tarot died out in Italy but survived in France and Switzerland. When the game was reintroduced into northern Italy, the Marseilles designs of the cards were also reintroduced to that region.

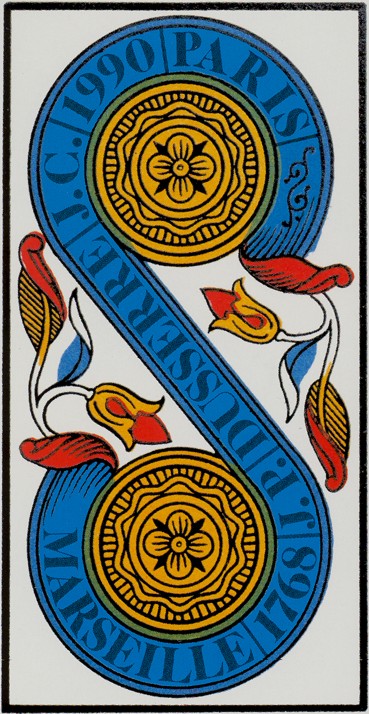

The name Tarot de Marseille is not of particularly ancient vintage; it was coined at least as early as 1889 by the French occultist Papus (Gérard Encausse) in Chapter XI of his book le Tarot des bohémiens (Tarot of the Bohemians), and was popularized in the 1930s by the French cartomancer Paul Marteau, who used this collective name to refer to a variety of closely related designs that were being made in the city of Marseille in the south of France, a city that was a centre of playing card manufacture, and were (in earlier, contemporaneous, and later times) also made in other cities in France. The Tarot de Marseille is one of the standards from which many tarot decks of the 19th century and later are derived.

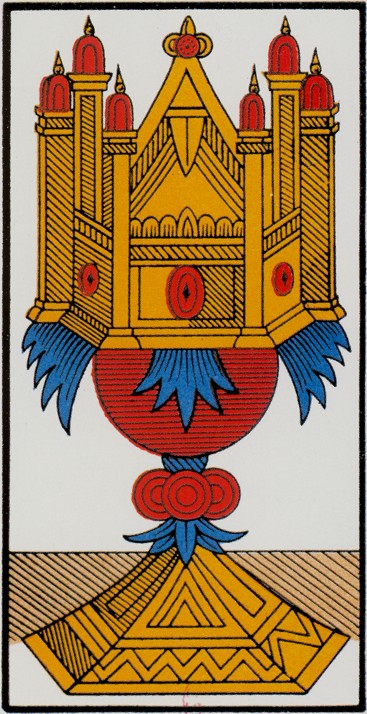

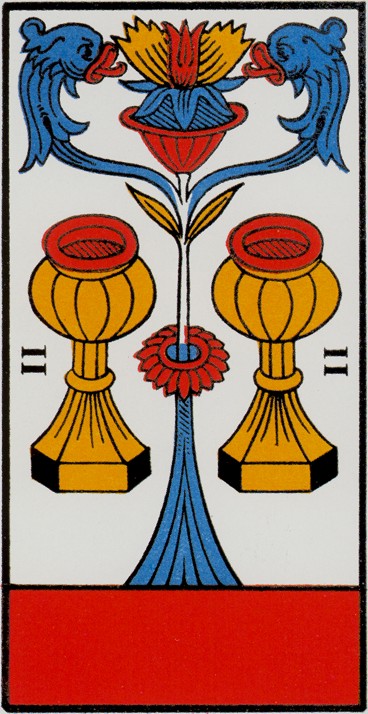

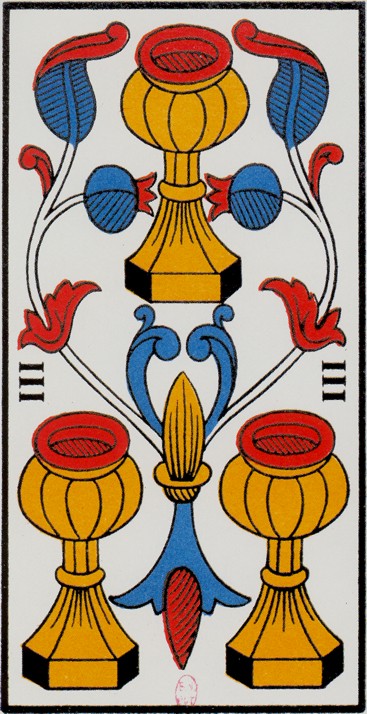

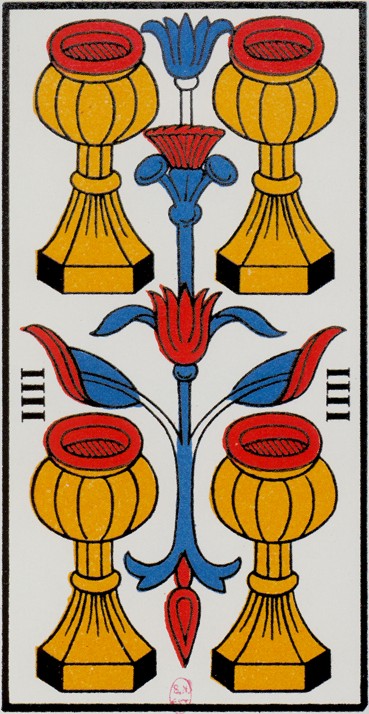

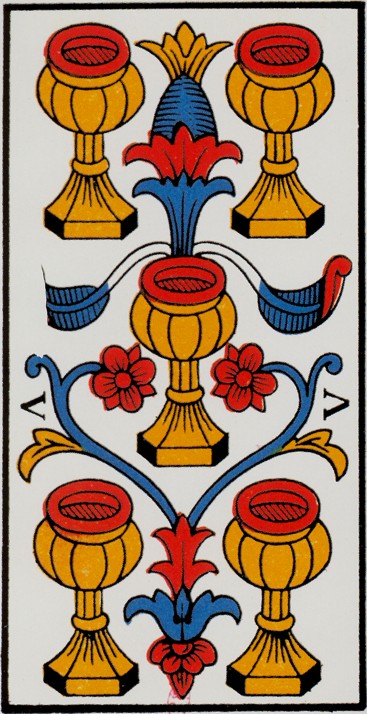

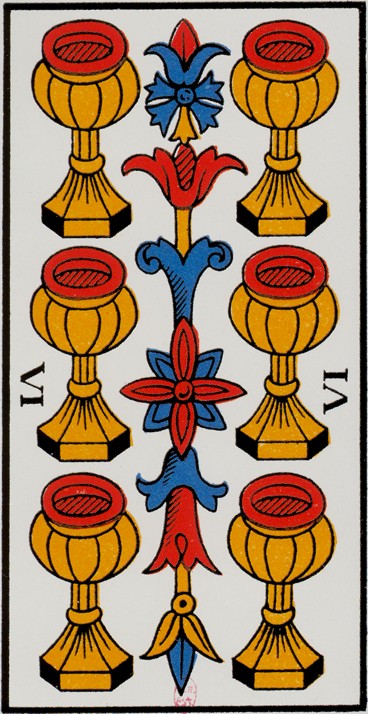

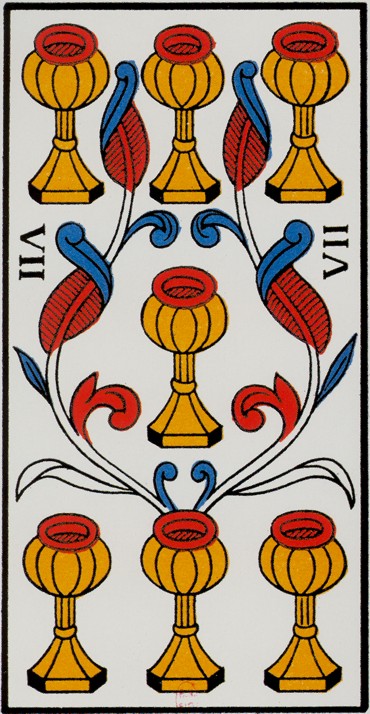

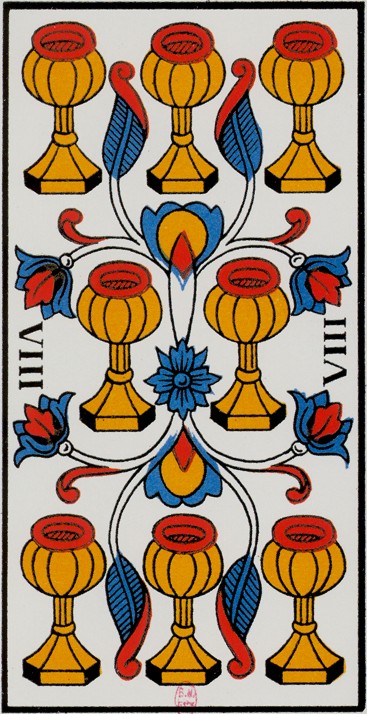

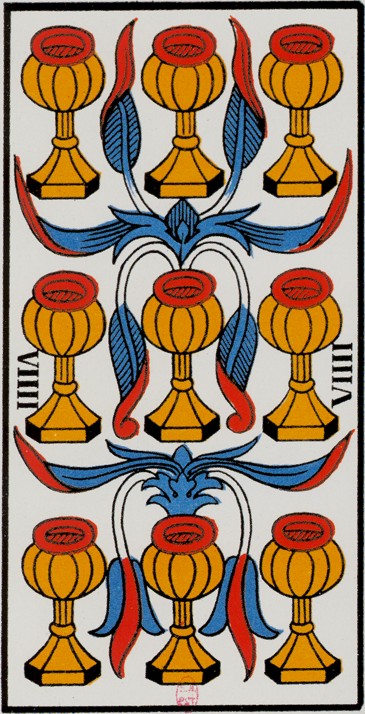

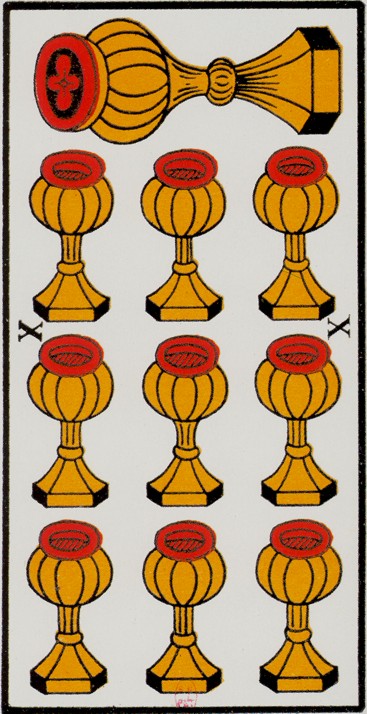

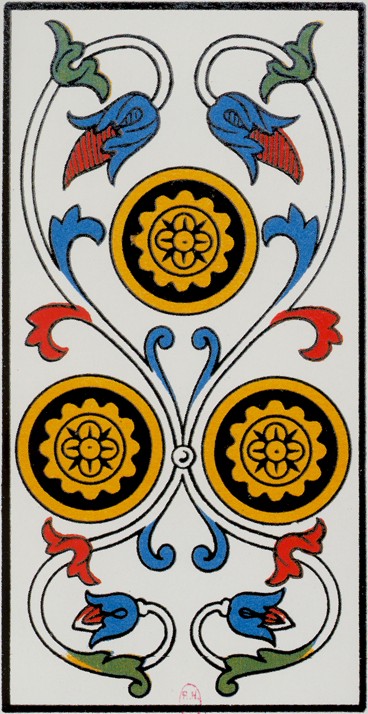

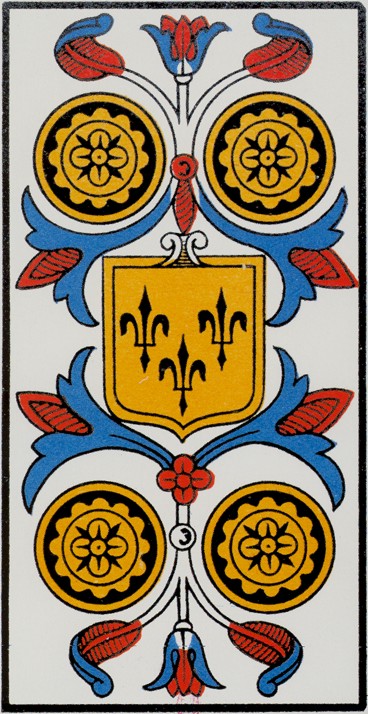

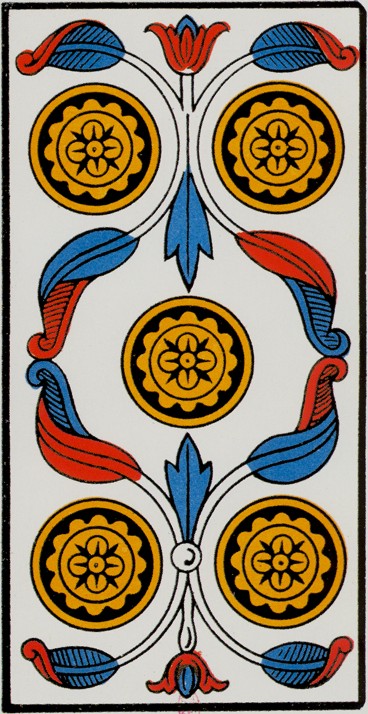

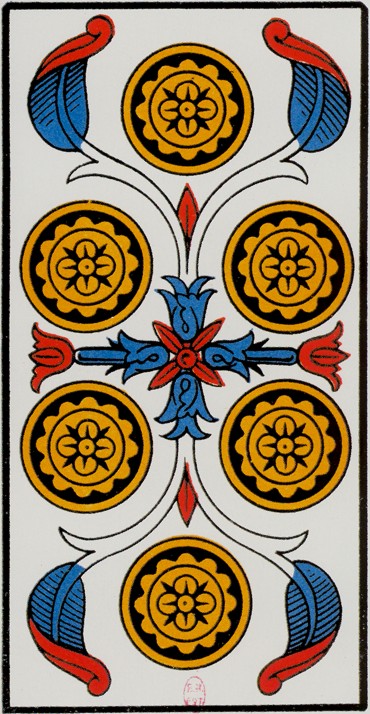

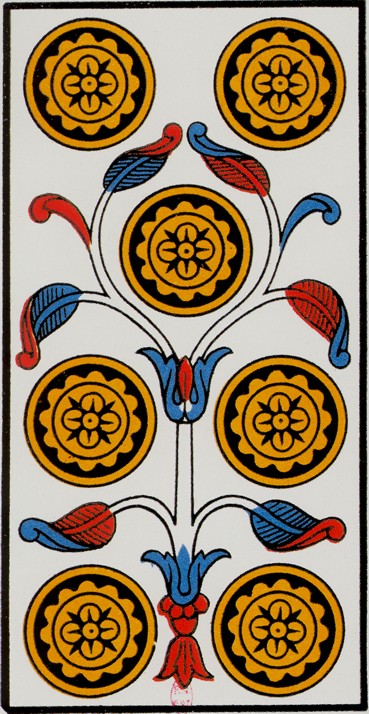

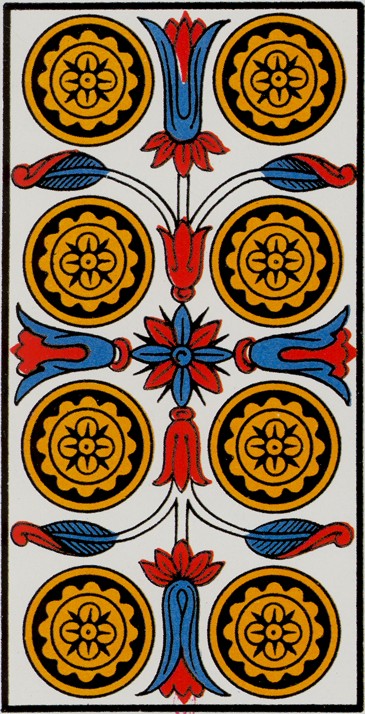

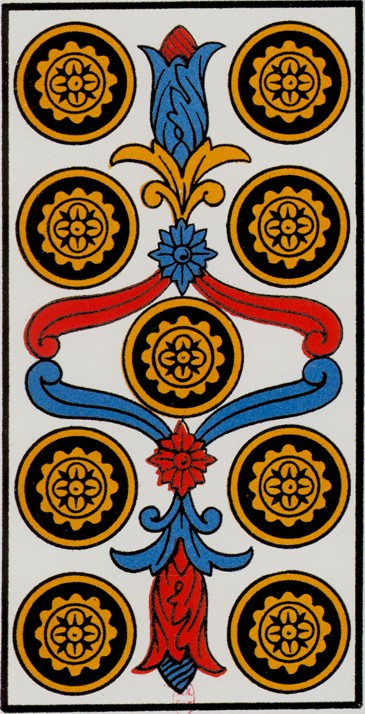

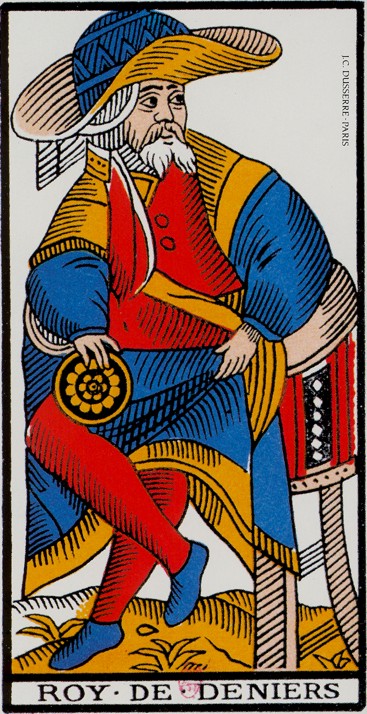

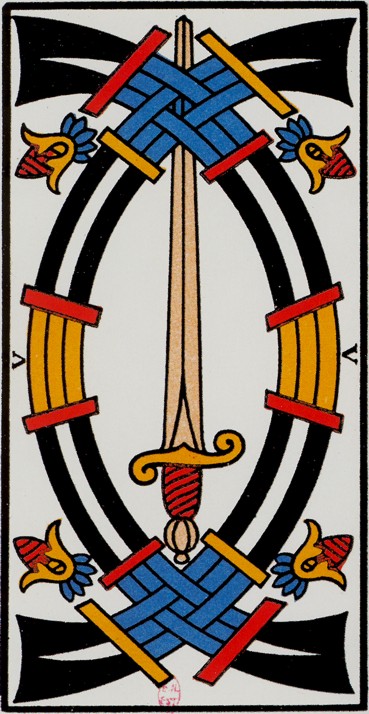

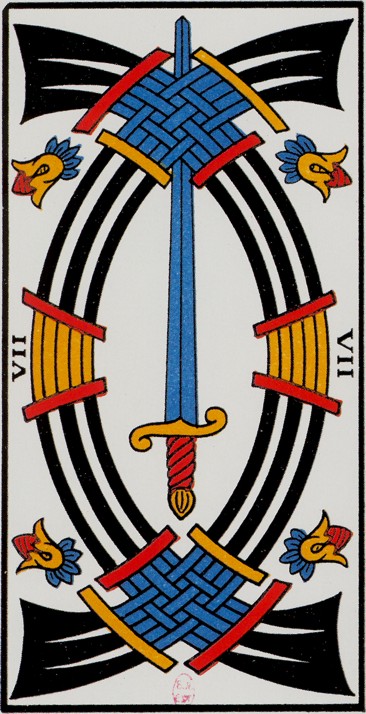

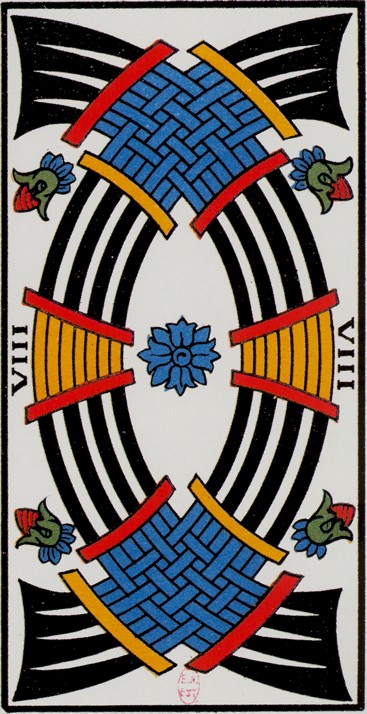

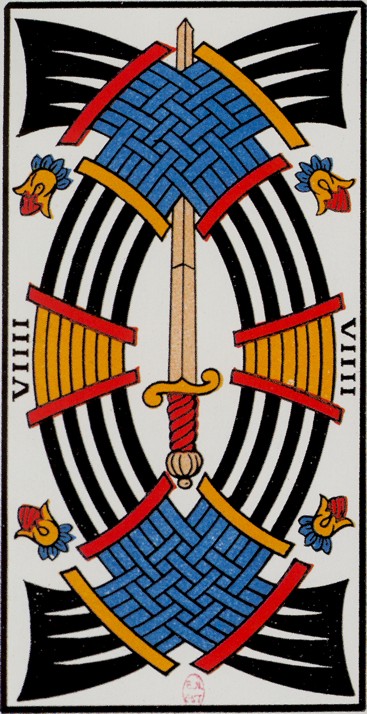

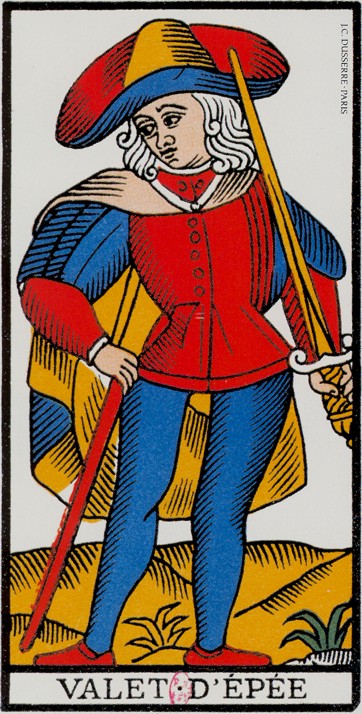

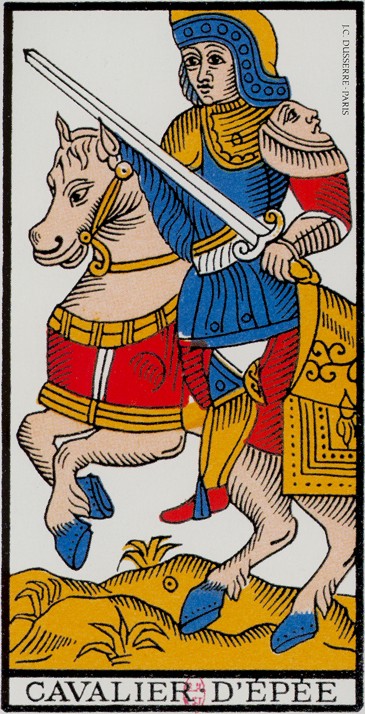

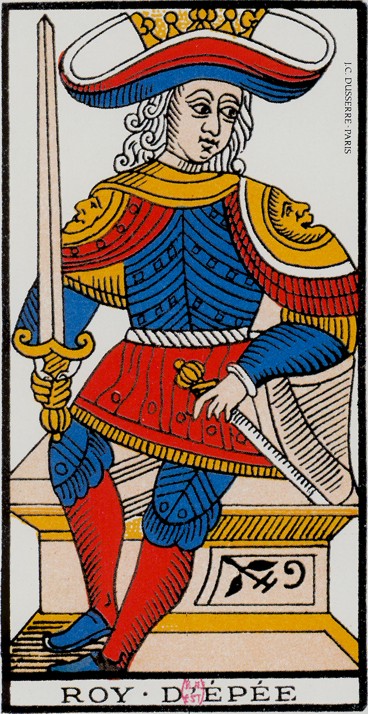

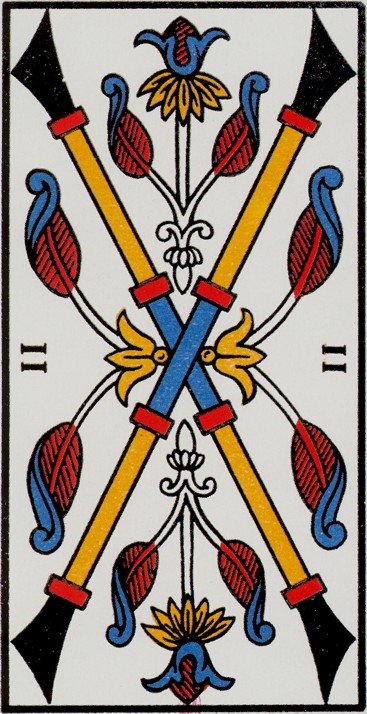

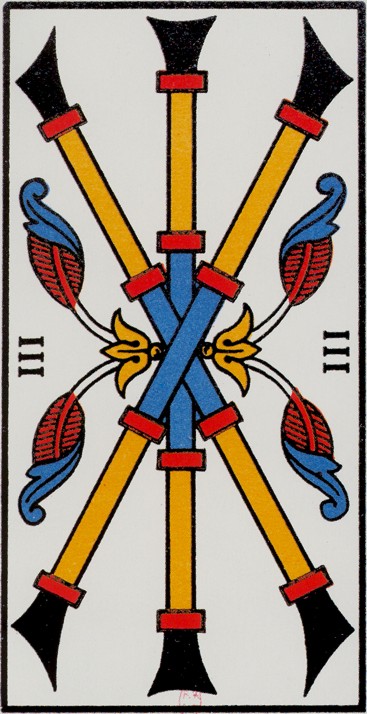

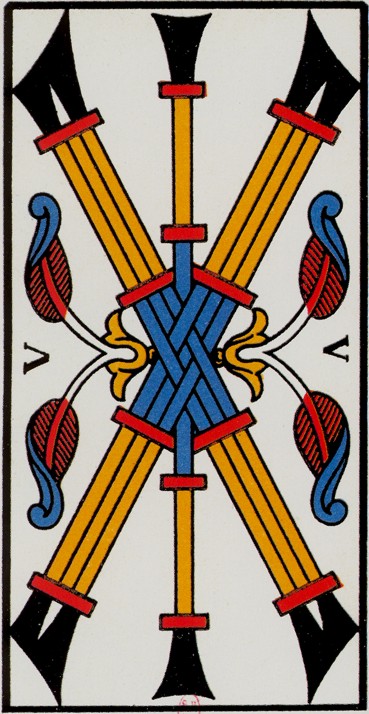

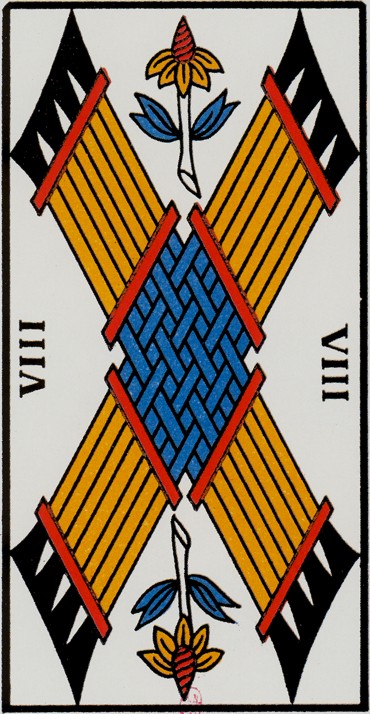

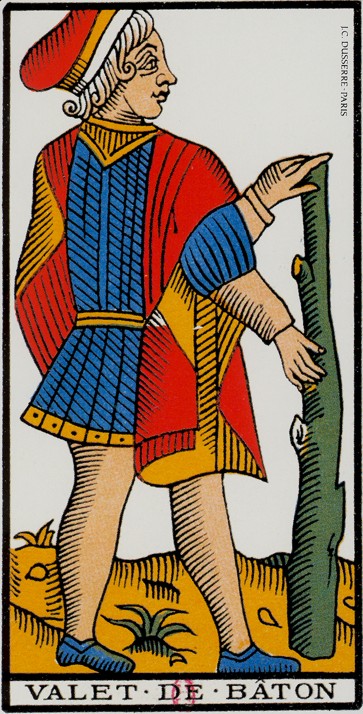

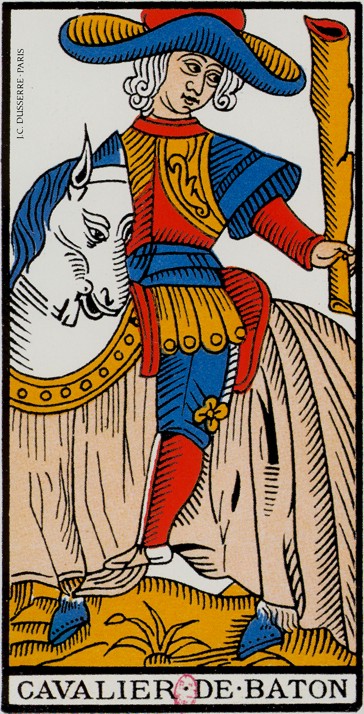

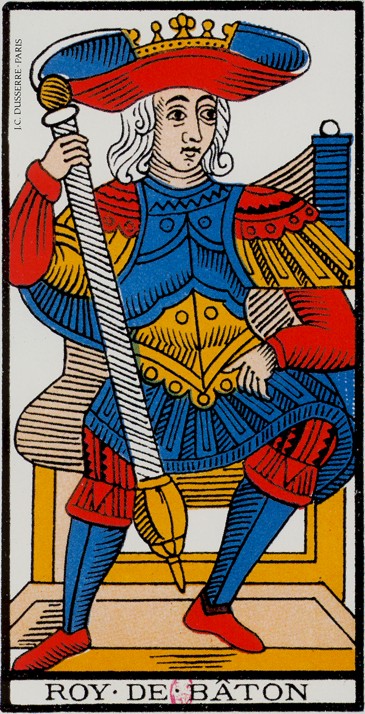

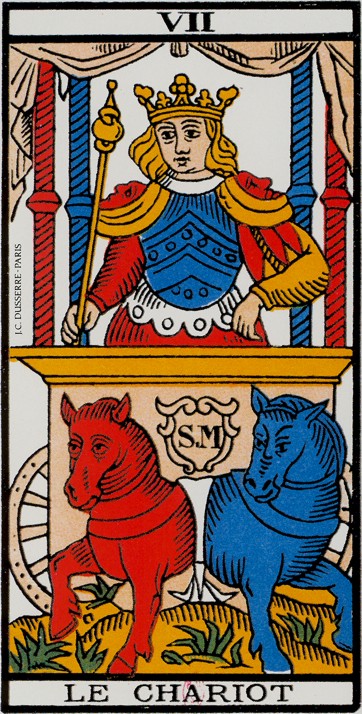

Like other Tarot decks, the Tarot de Marseille contains fifty-six cards in the four standard Suits. In French-language versions of the Tarot de Marseille, those suits are identified by their French names of Bâtons (Rods, Staves, Sceptres, or Wands), Épées (Swords), Coupes (Cups), and Deniers (Coins). These count from Ace to 10.

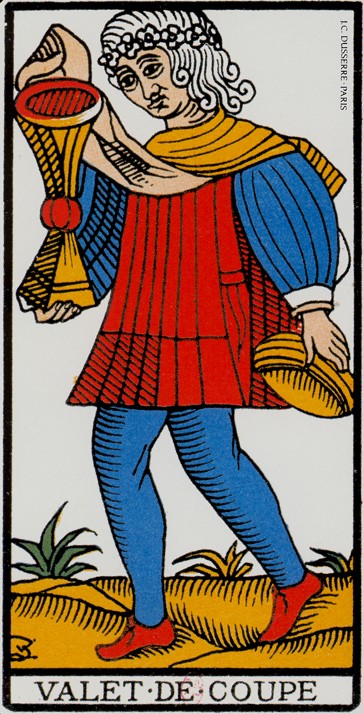

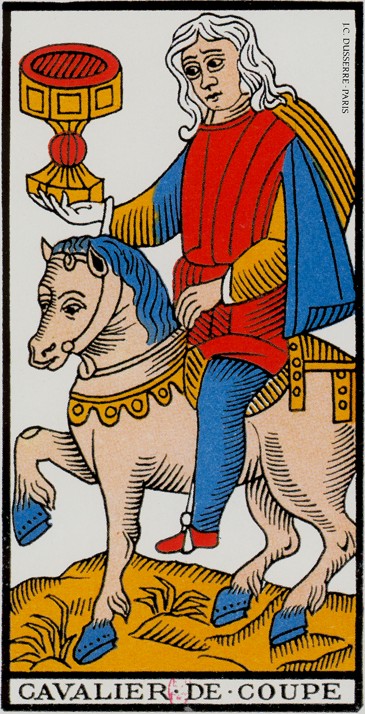

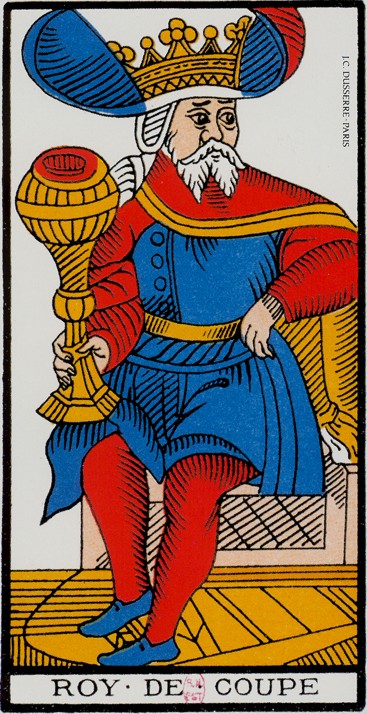

As well, there are four court cards in each suit: a Valet (Knave or Page), Chevalier or Cavalier (Horse-rider or Knight), Dame (Queen) and Roi (King). Occultists (and many tarot readers nowadays, whether English- or French-speaking) call this series the Minor Arcana (or Arcanes Mineures, in French). The court cards are sometimes called Les Honneurs (The Honors) or Les Lames Mineures de Figures (The Minor Figure Cards) in French, and the “Royal Arcana” in English.

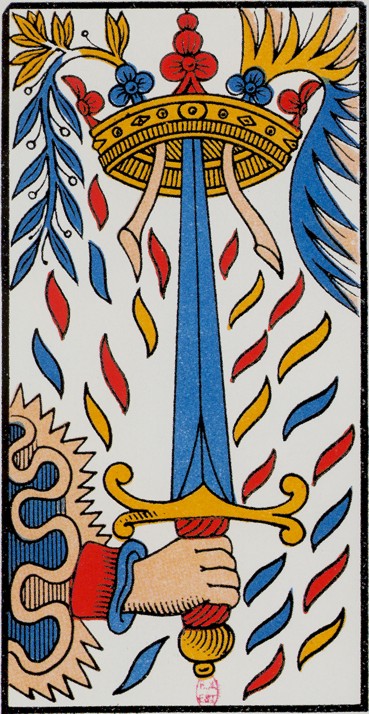

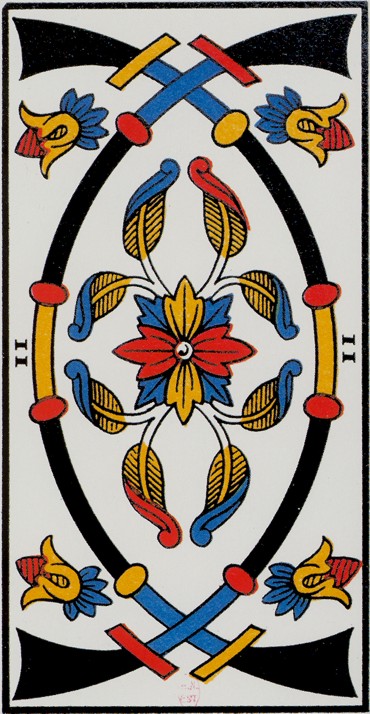

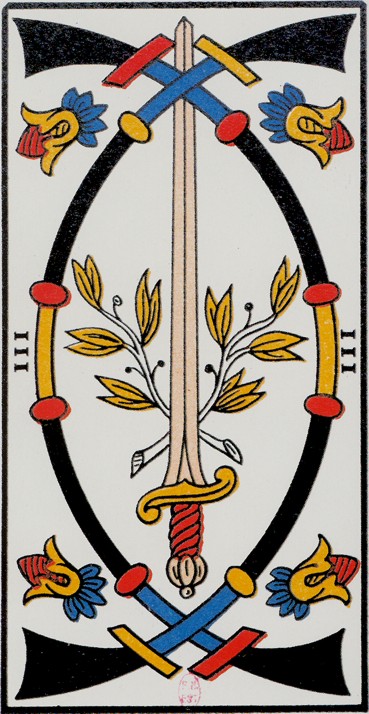

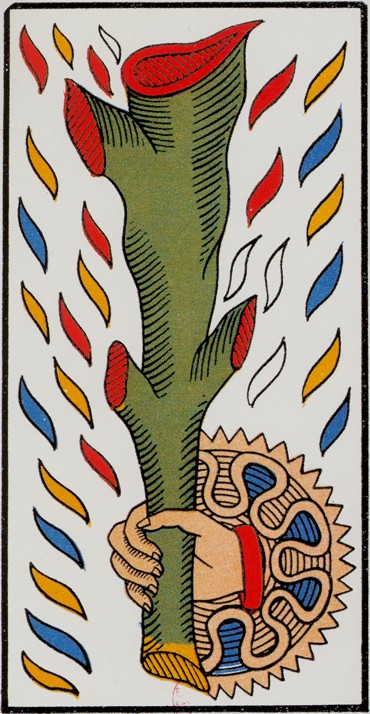

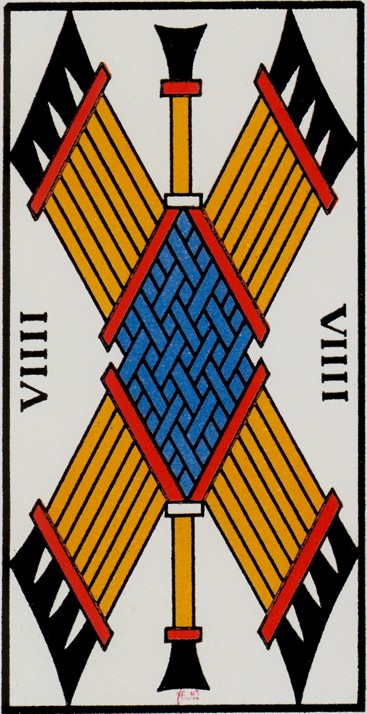

In the Tarot de Marseille, as is standard among Italian suited playing cards, the pip cards in the suit of swords are drawn as abstract symbols in curved lines, forming a shape reminiscent of a mandorla. On the even numbered cards, the abstract curved lines are all that is present. On the odd numbered cards, a single fully rendered sword is rendered inside the abstract designs. The suit of wands is drawn as straight objects that cross to form a lattice in the higher numbers; on odd numbered wands cards, a single vertical wand runs through the middle of the lattice. On the tens of both swords and batons, two fully rendered objects appear imposed on the abstract designs.[1] The straight lined wands and the curved swords continue the tradition of Mamluk playing cards, in which the swords represented scimitars and the wands polo mallets.

The recent documentary “Les mystères du Tarot de Marseille” (Arte, 18 dévrier 2015) claims that the work of Marsilio Ficino can be credited as having inspired imagery specific to the Marseilles.

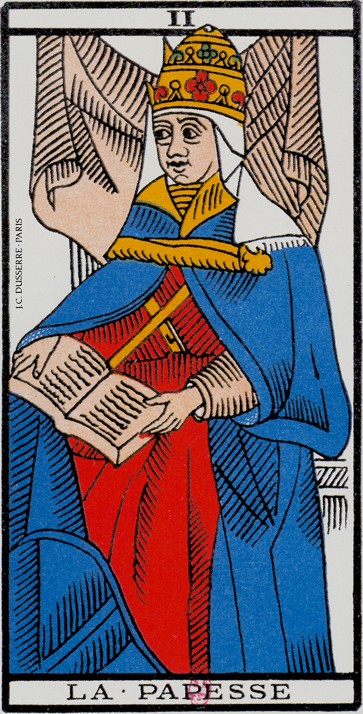

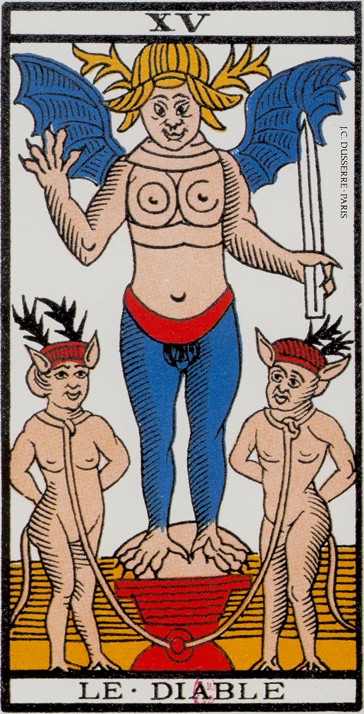

The Papess card has sparked controversy because of its portrayal of a female pope. There is no solid historical evidence of a female pope, but this card may be based around the mythical Pope Joan. Many variant names have been used to avoid such controversy, including Juno, The Spanish Captain and The High Priestess.

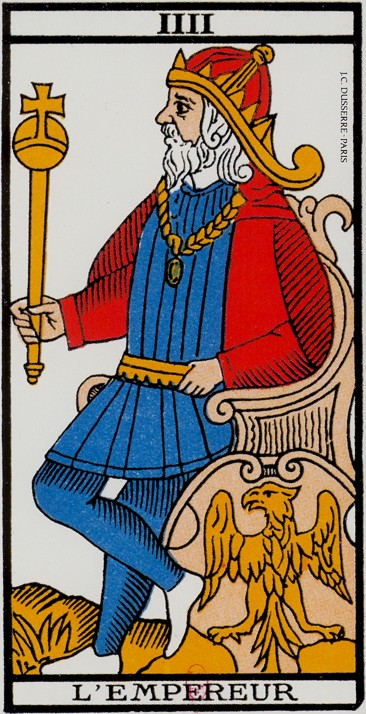

One variant of the Tarot de Marseille, now called the Swiss Tarot or the Tarot of Besançon, removes the controversial Papess and Pope and, in their stead, puts Juno with her peacock, and Jupiter with his eagle. More recent decks, following a suggestion by Court de Gébelin, often rename the Papess as the “High Priestess”, and the Pope as the “Hierophant” (Greek > “High Priest”). During the French Revolution, the Emperor and Empress cards became the subject of similar controversies and were displaced by Grandfather and Grandmother.

Just as to the east of the French centre is the Besançon/Swiss Junon-Jupiter (II-V) variant, so to the north are variants in the Flemish decks. The Papesse is replaced with Le ‘Spagnol Capitano Eracasse (Italian > the ‘Spanish Captain’ Fracasso, a stock character from Commedia dell’arte). The Pope. often depicted holding an orb or a covered communion chalice, is replaced by Bacus (Bacchus, the Greek god of wine) holding a wine cup or bottle and a fruited vine cane or bunch of grapes while astride a beer barrel or wine cask.

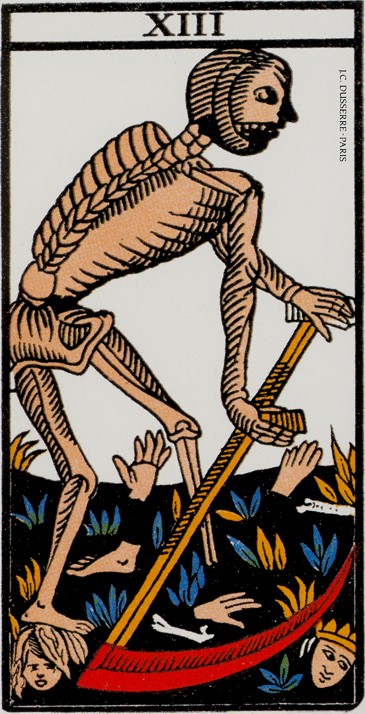

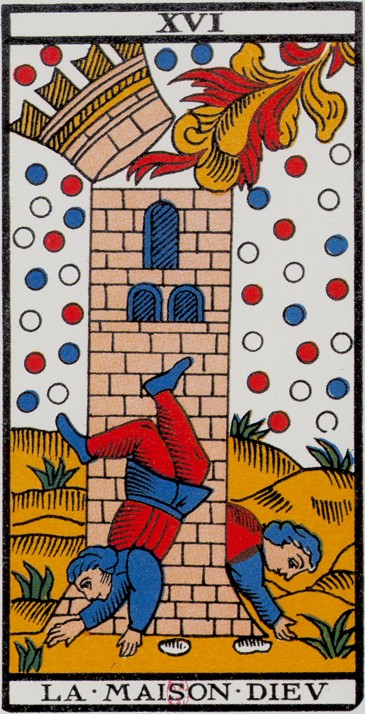

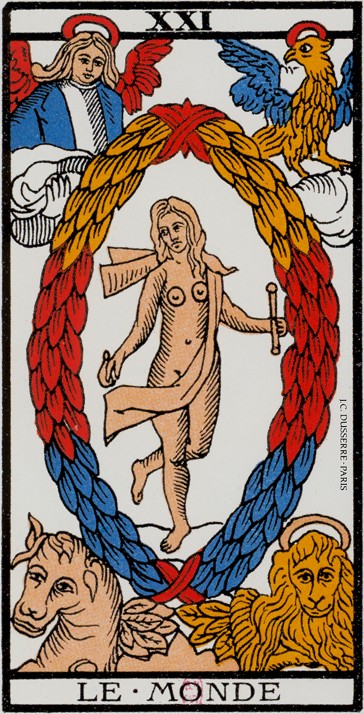

The XIII card is generally left unnamed in the various old and modern versions of the Tarot de Marseille, but it is worth noting that in the Noblet Tarot de Marseille (circa 1650), the card was named LAMORT (Death). In at least some printings of the French/English bilingual version of the Grimaud Tarot de Marseille, the XIII card is named “La Mort” in French and named “Death” in English.

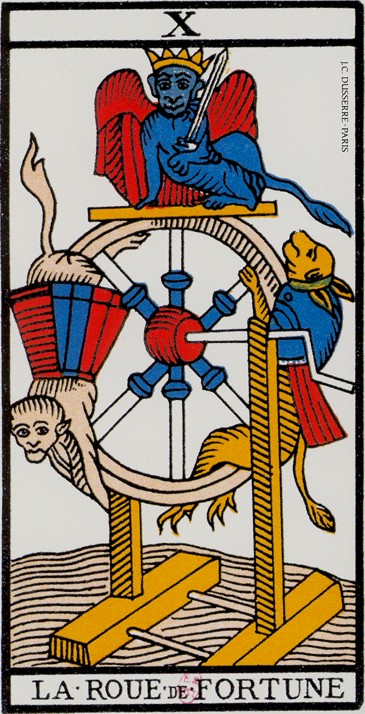

Each card, whether in the major arcana or minor arcana, was originally printed from a woodcut; the cards were later coloured either by hand or by the use of stencils. One well-known artisan producing tarot cards in the Tarot de Marseille style was Nicolas Conver, who produced one early attested deck in 1760. Other early attested decks in the Tarot de Marseille family of decks include Noblet’s (circa 1650) and Dodal’s (circa 1701). The chief use of the deck originally was to play the game of tarot, also known as tarock [German] or tarocco [Italian]; the use of tarot in divination is first attested in the 18th century in the journals of Giacomo Casanova.

It was the Conver deck, or a deck very similar to it, that came to the attention of Antoine Court de Gébelin in the late 18th century. Court de Gébelin’s writings, which contained much by way of speculation as to the supposed Egyptian origin of the cards and their symbols, called the attention of occultists to tarot decks. As such, Conver’s deck became the model for most subsequent esoteric decks, starting with the deck designed by Etteilla forward. Cartomancy with the Tarot was definitely being practised throughout France by the end of the 18th century; Alexis-Vincent-Charles Berbiguier reported an encounter with two “sibyls” who divined with Tarot cards in the last decade of the century at Avignon.

Tarot de Marseille

0 comments on “Tarot de Marseille”

1 Pings/Trackbacks for "Tarot de Marseille"

[…] arcana. Known as the “Arcanes du Tarot kabbalistique”, it followed the designs of the Tarot de Marseille closely but introduced several alterations, incorporating extant occult symbolism into the cards. […]